Paul – faithful follower of Jesus or inventor of a new religion?

The Old Testament is filled with numerous commandments (‘mitzvot’ in Hebrew), 613 in total to be precise, and in Judaism one’s standing as a believer is measured by one’s keeping of the commandments. Total obedience to the Law of Moses is God’s covenant with the children of Israel and the core message that all the Israelite Prophets brought. By contrast, Christianity teaches that whether you are Jew or Gentile, one’s standing as a believer is not based on rigorously keeping God’s laws, but rather on belief in Jesus. From this point of view, you can say that Judaism is characterised by the Law, and Christianity by its lack of it. We can see that a major distinguishing factor between these religions is that of their attitude towards the Law of Moses, and it’s all because of one man – Paul. He is seen by Christians as an Apostle of God and he claims that his message was divinely sanctioned and represents a new covenant that replaced the old Mosaic one.

Just what did Jesus himself teach about the Mosaic Law? This is a question that many don’t stop to consider. Is the message of Jesus and that of Paul one and the same? What was the outlook of the earliest followers of Jesus on the Law? These are just some of the questions that we are going to explore in this article, and the answers shake the very foundation of Christianity.

Jesus Practised and Preached the Law of Moses

Christians today view Christianity as representing a complete and total break from Judaism with the arrival of Jesus. Nonetheless, if we analyse the teachings of Jesus, we will find overwhelming evidence that, throughout his ministry, he was a Torah observant, obeying the Law and teaching others to do the same. His attitude towards the Law is exemplified in the Sermon on the Mount where he makes his position unequivocally clear:

We can see that Jesus links righteousness and success in the Hereafter with obedience to the Law. Now, Christians might argue that Jesus is simply saying that the entire Law will be in effect until he dies (“until everything is accomplished”). But Jesus is saying more than that; his followers must obey and teach the Law. None of it will pass away until the world is destroyed (“until heaven and earth disappear”). Jesus does not say, “Keep the Law until I die.” He says he did not come to destroy the Law; it is still in effect and will be, for as long as heaven and earth last. This sermon was perfectly in line with the teachings of the Old Testament:

Just how righteous does one have to be? Jesus set a standard in his sermon. One’s obedience to the Law has to exceed that of the Pharisees and teachers of the Law (“unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven”). But why is this the case? There was a real problem with the righteousness of the religious leaders of his day. The heart of the matter was that their righteousness was defective, in that it was external only. They appeared to obey the Law to those who observed them, but broke God’s Law inwardly, where it couldn’t be seen by others. Notice Jesus’s scathing denunciation of their hypocrisy in making a show of religion:

Where many Christians jump to wrong conclusions about Jesus and the Law is in his confrontations with these religious leaders. Jesus was not pitting himself against the Mosaic Law. These confrontations were never over whether to keep the Law, only over how it should be kept. It must be noted that Jesus fully acknowledged the teaching authority of the Pharisees and advised others to follow what they teach, but not to act hypocritically as they did:

In actual fact, Jesus went a step further and extended the parameters of the Law. His move was to give a deeper and fuller understanding, to cover underlying attitudes and not just behaviours. For example, one of the most important commandments was not to murder. Jesus increased the scope of the Law to cover not only the act of murdering someone, but also anger towards others:

So far from abolishing the Law, Jesus actually made its practice even more rigorous.

How Jesus’s Earliest Followers Viewed the Law

In addition to the life and teachings of Jesus, there is further corroborating evidence for his pro-Law stance. It’s to be found in the beliefs and practices of his immediate followers. The Book of Acts attests to the apostles’ regular attendance at the Jewish Temple:

If these early Christians had been breaking the Jewish religious laws, then they would not have been welcome in the temple courts, and they would not have enjoyed the favour of the other Jews who had come to the temple to worship.

Here the description of the disciple Ananias as a “devout observer of the law” chosen by God to heal and baptise Saul (Paul) clearly confirms that the followers of Jesus had not yet abandoned the observance of the Law:

We can see that Ananias was living in Damascus, far away from the Jerusalem Temple which was the centre of Jewish religious life, and yet he was still devout to the Law. Obviously, he considered obedience to the Law to be important enough, despite living outside of the Holy Land.

This attitude also extended to the close family members of Jesus. We are told that James is the flesh and blood brother of Jesus: “Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? Isn’t his mother’s name Mary, and aren’t his brothers James, Joseph, Simon and Judas?” [Matthew 13:55]. James preached a message of total obedience to the Law. He believed that one should not comply with the Law partially, keeping some commandments and breaking others. Rather, one should try and keep all of it as breaking part of it is equivalent to breaking all of it:

James’s teachings mirror those of Jesus in his Sermon on the Mount. James was not just the brother of Jesus, but also a senior leader among Christians. Paul acknowledges his seniority: “James, Cephas and John, those esteemed as pillars, gave me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship…” [Galatians 2:9] Some years after his conversion, Paul pays a visit to the elders in Jerusalem. By this time many thousands of Jews had become believers in Jesus. The elders of Jerusalem describe (in a seemingly proud boast) the state of the believing Jews in their large congregation as being “zealous for the Law”:

We’ve seen that the earliest believers in Jesus were, for all intents and purposes, Jewish. At this early stage, Christianity was just another movement within Judaism, not a separate religion. This is another piece of evidence for the Law-centric teachings of Jesus, for if the students of Jesus, his apostles and family members, had this positive attitude towards the Law, then it stands to reason that their teacher, Jesus, also had it.

Two branches of Christianity begin to emerge

Soon after Jesus departed an event took place that would change the face of Christianity, and the world, forever. According to the New Testament, Saul of Tarsus, or Paul as he is more commonly known, was a zealous Pharisee who intensely persecuted the followers of Jesus. Although he never met Jesus in person, he claims to have encountered him in a mystical vision on his travels and received instructions that he should stop persecuting Christians. Paul was to be God’s chosen instrument to proclaim the message of Jesus to the Gentiles.

Immediately afterwards, Paul began to preach to the Gentiles about Jesus. With Gentiles becoming Christian in large numbers for the first time, an important question now arose: what is their status with regard to the Law of Moses, did it apply to Jew and Gentile converts alike? In other words, must non-Jews become Jewish in order to become Christian? In the eyes of Jesus’s original Jewish followers, any Gentile who wanted to become a follower of Jesus was, in fact, becoming a follower of Judaism. But as Paul’s evangelism brought in ever-larger numbers of Gentile converts, the issue of just how far these converts had to go in order to become followers became very contentious. New Gentile believers who were men would, quite understandably, want to put off circumcision, if at all possible. Jewish believers, on the other hand, were concerned that relaxing the circumcision requirement could potentially lead to an abandonment of all the requirements of the Mosaic Law. As Paul’s ministry grew, the issue became increasingly urgent. Was any relaxation of the Law of Moses possible in these new circumstances? These are the questions that the Jerusalem Council was called to resolve. Chapter 15 of the Book of Acts goes into detail about this significant event:

We can see that this issue over the Gentiles and the Law was causing friction between Paul and other believers. The Council is convened and Paul attends it, along with the apostles and other elders of the Jerusalem congregation. Paul brings the Jerusalem congregation the news of his evangelising to the Gentiles and their entering into the faith:

The Pharisaic Christians adopted a very strict view:

Circumcision was closely linked to following the Jewish law. The strict view among the Pharisaic Christians was that it was necessary for Gentiles to be circumcised and keep the whole of the Law of Moses. Others, such as the disciple Peter, took a much more lenient view. It is James who proposes the compromise:

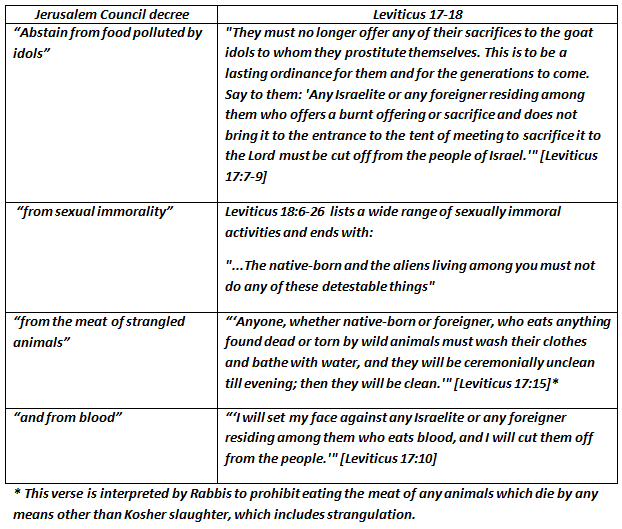

We can see that James decreed that Gentiles don’t have to be circumcised, though they should abstain from eating food offered to idols, strangled animals and blood, and from committing fornication. These are all ancient regulations found in the Law of Moses. In the section of the Law given in Leviticus 17-18, known as the Holiness Code, these same requirements are listed:

It is quite telling that James looked to the Old Testament for guidance on this issue. Notice that the Old Testament verses above apply to Israelites and “aliens” (foreigners or strangers) living among them. Rather than cancelling or withdrawing these Old Testament regulations, their scope is extended by applying them to the Gentile believers who do not live among the Israelites. Clearly, in the sight of James, the Law was considered to be important. A question then naturally arises: why didn’t James apply the whole of the Law to the Gentile believers, and does this prove that the Law was ultimately meant to be abolished? The answer is absolutely not, because God’s covenant as a whole in the Old Testament was specifically with the Israelites. What James did was take the four ancient commands from the Old Testament which applied to “aliens” living amongst the Israelites and logically equate them to the Gentile believers who were viewed as outsiders.

The apostles and elders agreed with the decision made by Jesus’s brother James which indicates that James held a very senior position in the Jerusalem congregation. They put his decree in a letter that was to be distributed to the Gentile believers via Paul and his companion Barnabas:

Then the apostles and elders, with the whole church, decided to choose some of their own men and send them to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas. They chose Judas (called Barsabbas) and Silas, men who were leaders among the believers. With them they sent the following letter:

The apostles and elders, your brothers,

To the Gentile believers in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia:

Greetings.

We have heard that some went out from us without our authorization and disturbed you, troubling your minds by what they said. So we all agreed to choose some men and send them to you with our dear friends Barnabas and Paul— men who have risked their lives for the name of our Lord Jesus Christ. Therefore we are sending Judas and Silas to confirm by word of mouth what we are writing. It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us not to burden you with anything beyond the following requirements: You are to abstain from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals and from sexual immorality. You will do well to avoid these things.

Farewell. [Acts 15:22-29]

It’s important to spend some time analysing this monumental event as it has many implications on the origins of modern Christianity. First, the outcome of this Council is that there was now a two-tiered church; one of Jewish believers in Jesus obedient to the whole of the Law, and another of Gentile believers who were only under obligation to keep those parts of the Law as decreed by the Council. We’ve seen that this decision was not arrived at easily, for there were many different opinions on the question of whether the Gentiles had to obey the Mosaic Law. Ultimately, a middle position was adopted, with James making the authoritative decision that Gentiles should follow some aspects of the Law, not all. It is quite telling that James and the other Law-observant believers looked to the Old Testament for guidance on this issue. We’ve seen that rather than cancelling or withdrawing the Old Testament legislation that governed Israelites and aliens (foreigners or strangers) among them, James and the apostles actually extended their scope by applying them to Gentile believers not living among the Israelites. So, the Law was obviously still considered to be important in the eyes of the apostles and elders even after the departure of Jesus. Had Jesus habitually violated the Law, or had Jesus instructed them that it was okay to do so, then no-one would have objected to a complete abandonment of the Law by the Gentiles. But Jesus was Law-observant, as were all of his earliest followers.

One final point that needs to be covered about the Council is the following comment that James made about Simon (another name for the disciple Peter):

Simon has described to us how God first intervened to choose a people for his name from the Gentiles. The words of the prophets are in agreement with this, as it is written:

“After this I will return

and rebuild David’s fallen tent.

Its ruins I will rebuild,

and I will restore it,

that the rest of mankind may seek the Lord,

even all the Gentiles who bear my name,

says the Lord, who does these things”—

things known from long ago. [Acts 15:14-18]

Here James quotes the Old Testament (Amos 9:11-12) in order to make sense of the situation they were now facing with the Gentiles. He quotes a prophecy which describes how the Israelites will become fallen (“David’s fallen tent”) and how Gentiles will have the opportunity to seek God. It’s important to note that this prophecy says nothing about the end of the Mosaic Law, or that Jewish believers in Jesus no longer need to practice the Mosaic Law. An interesting point is that the Book of Acts has James quote from the Septuagint version of the Old Testament. If one compares the Hebrew Masoretic Text version of the Old Testament for the same prophecy, we find the following:

“In that day

I will restore David’s fallen shelter—

I will repair its broken walls

and restore its ruins—

and will rebuild it as it used to be,

so that they may possess the remnant of Edom

and all the nations that bear my name,”

declares the Lord, who will do these things. [Amos 9:11-12]

If you compare these two versions of the prophecy, they are saying very different things. Whereas the Septuagint version of Amos 9:11-12 that is quoted in Acts says that Gentiles will one day have the opportunity to seek God, the Hebrew Masoretic Text version makes no mention of this. In fact it says the opposite, it states that the Israelites will become fallen (“David’s fallen shelter”) and that they will be rebuilt and “possess the remnant of Edom”. Edom was an ancient Gentile kingdom in the Middle East. In other words, God will restore the Israelites and make them possess the Gentiles.

The Parting of the Ways

We’ve seen that on the Jerusalem Council, Paul submitted to the decision taken by the apostles and elders that Gentile believers were to observe some aspects of the Law. Now, when we turn to Paul’s own writings, a troubling picture emerges. What is clear from Paul’s personal writings is that at some point after the Jerusalem Council, he started preaching a radically different message from that of the Jerusalem congregation. Whereas Jesus and his earliest followers taught righteousness through the Law, Paul started to promote a message of righteousness apart from the Law:

So, according to Paul, no-one can be justified by obedience to the Law. A question then naturally arises: if no-one can become righteous through the Law, then why did God bother to give it to Moses in the first place? Paul offers the following reason:

Apparently, the purpose of the Law was to make man realise that he is guilty before God. In other words, it’s to prove to us that it’s impossible to keep the Law. This not only goes against Jesus, who believed that it was possible to keep, as he preached a message of total obedience to it, but also the Old Testament where God is clear: it is not too difficult to obey the commandments of the Law:

Paul even went so far as to say some very negative things about the Law. Here he calls it a curse:

While Paul acknowledged his past zealousness in obeying the Law, he regarded all such efforts as garbage:

Again, such negativity is at odds with what Jesus taught about how obedience to the Law makes one greatest in the kingdom of heaven, as well as what the Old Testament teaches about obedience to the Law bringing God’s blessing and prosperity:

Now, one may think that all such writings by Paul were directed to Gentiles only and do not apply to Jewish believers in Jesus. But this is not the case, as Paul clearly stated that in his eyes there is no longer any distinction between Jew and Gentile. In fact, he thought that the only Israel that God recognises anymore is a spiritual Israel made up of both Jew and Gentile who are no longer bound by the Law and live primarily by faith:

It must be reiterated that Paul’s anti-Law sentiment isn’t just restricted to Gentile Christians; he applied it to Jewish believers in Jesus as well. This is in direct conflict with the apostles and elders who practised the Law and expected other Jewish followers of Jesus to do the same. Now Christians may argue that the Jerusalem Council decree was merely provisional or temporary. They may think that, yes, initially Paul agreed with the apostles and elders that Gentiles had to obey some aspects of the Law, but then at a later stage they all changed their opinions. However, this is not the case, as we see that towards the end of his life, Paul visited Jerusalem again and met with the same apostles and leaders. During this visit, Paul re-confirmed his commitment to the Jerusalem Council decree:

When we arrived at Jerusalem, the brothers and sisters received us warmly. The next day Paul and the rest of us went to see James, and all the elders were present. Paul greeted them and reported in detail what God had done among the Gentiles through his ministry. When they heard this, they praised God. Then they said to Paul:

“You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law. They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs. What shall we do? They will certainly hear that you have come, so do what we tell you. There are four men with us who have made a vow. Take these men, join in their purification rites and pay their expenses, so that they can have their heads shaved. Then everyone will know there is no truth in these reports about you, but that you yourself are living in obedience to the law. As for the Gentile believers, we have written to them our decision that they should abstain from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals and from sexual immorality.”

The next day Paul took the men and purified himself along with them. Then he went to the temple to give notice of the date when the days of purification would end and the offering would be made for each of them. [Acts 21:17-26]

Notice the charge that the elders brought to Paul’s attention, “They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses”. By submitting to the elders’ command to undergo a purification ritual, Paul made a public declaration that he was loyal to the Law of Moses and innocent of all such allegations. Also, notice that the elders re-iterated their decree from the Jerusalem Council; the Old Testament laws pertaining to “food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals and from sexual immorality” were still binding on Gentile believers. As readers, we are left with a perplexing situation – how is it that Paul denies the allegations of abandoning the Law and submits to the decree of the church elders in person, but preaches a message of Lawlessness for both Jews and Gentiles in his writings? It seems that either Paul is being deceitful to the elders, or that the history of the early Church, as it is recorded in the New Testament, is unreliable. Both scenarios are highly problematic for Christianity.

In any case, despite Paul’s willingness to undergo the self-purification ritual, he continued to inspire hostility in those ‘zealous for the Law’ – who, a few days later, attacked him in the Temple. “This”, they proclaim, “is the man who teaches everyone everywhere against our people and our Law” [Acts 21:28]. The ensuing riot is no minor disturbance:

Paul goes on to be rescued in the nick of time by some Roman troops who arrest him. Paul is subsequently put on trial in a Jewish court. Now the most fascinating thing about this whole episode is what is not said. At no point do we find the apostles of Jesus or elders, such as James, coming to Paul’s rescue during the mob attack, despite the fact they and their supporters numbered in the thousands in Jerusalem, nor do they come to his defence at his trial in the Jewish court. The explanation that they were perhaps scared to show their public support doesn’t work, as not only were they ardent supporters of the Law, a position that would have carried favour with the mob that attacked Paul, but these were men who were not afraid to stand up for the truth, even if it cost them their lives. This is according to Christian tradition which holds that many of these same apostles and elders would go on to be martyred for their beliefs at the hands of the pagan Roman Empire. Could it be that they believed that Paul was guilty of preaching against the Law, a fact we know to be true based on his personal writings? This would be the most rational explanation for their complete absence and seeming abandonment of Paul in the rest of the incidents that the Book of Acts narrates.

To demonstrate just how divergent the beliefs of Paul and the Jerusalem congregation had become, let’s focus for a moment on the issue of eating meat that has been sacrificed to idols. We’ve seen that the Jerusalem Council explicitly and unconditionally prohibited such a practice; yet, Paul breaks away and makes it permissible:

Paul’s reasoning is that since an idol is not a real thing, there is no harm in eating such meat. In doing so, Paul not only goes against the decision of the Jerusalem Council, but also other writers of the New Testament such as the author of the Book of Revelation where allusions to the Jerusalem Council decree can be found in multiple places:

It’s important to point out that the Book of Revelation comes at the end of the Bible and was the last book to be written, indicating that the prohibition on idol meat was still in place long after Paul authored his works. An outright prohibition on idol meat was even understood by Christian communities that existed after Paul. For example, the work known as The Didache is an anonymous early Christian treatise, dated by most modern scholars to the first century [1]. It’s seen as an early Christian church manual of sorts, and it has this to say on the permissibility of idol meat:

The early Christian apologist Justin Martyr, considered a saint in the Catholic Church, stated that Christians must “abide every torture and vengeance even to the extremity of death, rather than worship idols, or eat meat offered to idols.” [2]

In the clash of ideologies between Paul and the other believers, the emergence and evolution of what we call Christianity stood at a crossroads. Had the understanding and practices of the apostles and elders remained dominant, then there would be no Christianity at all today, only a particular species of Judaism. Yet, what was a heresy within the framework of Judaism was to become the orthodoxy of Christianity. Just how did we go from this situation, where Paul’s strand of Christianity was in a minority, to its position today, where it has absolute dominance and is considered the mainstream? While it’s beyond the scope of this article to delve too much into why Paul’s strand of Christianity ultimately ‘won out’, we will briefly mention some factors that may have served as catalysts. The destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE by the Romans would have no doubt been devastating to the Jerusalem Christians. The Temple was at the heart of their daily lives with its courts being used for important rituals such as worship and animal sacrifices. For Gentile converts, the rigour and legalism of Judaic Christianity stood in stark contrast to the freedom that Pauline Christianity offered, an attractive prospect to those coming from a hedonistic pagan background. We can only speculate as to why Pauline Christianity ultimately triumphed, but what we can be certain of is that it by no means represented the views of Jesus or those who were closest to him.

One oddity worth highlighting is the amount of ‘shelf space’ that Paul takes up in the New Testament. We’ve seen that Paul was very much a secondary figure in Acts, with leaders such as James, the brother of Jesus, taking much more senior and even dominant roles over him. Recall that Paul submitted to James’s decree at the Jerusalem Council, and even underwent the purification ritual at the command of the elders when he was confronted with the rumours of abandoning the Law. Yet, we have the strange situation of important figures like James having very little space in the New Testament, just one short letter that is the Epistle of James, whereas Paul by comparison dominates its pages; he is by far the most prolific New Testament writer, with almost half of the 27 New Testament books attributed to him. Such an imbalance reflects just how dominant Pauline Christianity had become by the time that the New Testament came to be canonised.

Conclusion

Who would have best understood the true message of Jesus, individuals such as Paul who never met him during his ministry on earth but claims to have experienced him in a vision, or the companions and family members of Jesus, such as his brother James, who were nearer to the source and knew Jesus personally in a way that Paul never did? Their understanding of his message is based on living and speaking with Jesus, and not unverifiable mystical experiences on the road to Damascus. We can look at their handling of the Jerusalem Council incident to get an insight into the mission of Jesus. Recall that there was initially a lot of disagreement among the apostles and elders as to how to deal with the sudden influx of Gentiles, specifically on the question of whether they must follow the Law. We saw that in coming to a decision, there was no reference to any of the teachings of Jesus. Why didn’t Jesus leave behind some instructions for how to deal with Gentiles? Apparently, the teachings of Jesus had nothing to say on this matter at all. In addition, if Gentiles originally were the target audience of Jesus and part of his mission all along, then, given the critical importance the Law had played in the lives of Jews since the time of Moses, surely the first question the apostles and elders would have asked Jesus is, “when we eventually come to evangelise to the Gentiles, what is their status with respect to the Law?” This is not what we find though; they had to convene a council in order to settle this question. This indicates that the sudden influx of Gentiles into the religion was an unplanned and unexpected turn of events and not something that Jesus had prepared them for, hence the friction that was happening and the disagreement over how to deal with them.

The Qur’an also supports this understanding as it reveals to us that Jesus was primarily sent to the Israelites and not the whole world: “He will teach him [Jesus] the Scripture and wisdom, the Torah and the Gospel, He will send him as a messenger to the Children of Israel…” [3:48-49]. Just as with the Trinity and the crucifixion, this is yet another stumbling block that the Qur’an removes, paving the way for the Jewish people to accept Jesus as the Messiah. The Qur’an presents a picture of Jesus that is in line with Jewish expectations of the Messiah, one whose target audience was the Israelites and one who would uphold the Law of Moses. Now, if Jesus was just another Israelite Prophet intended for the Israelites, then where does this leave Gentiles, the non-Jews? Are non-Jews really permanently outside of the fold of God’s covenant? The Jewish people don’t have a monopoly on God’s revelation, for Jesus brought glad tidings of the coming of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), a momentous individual who would be a light for the entire world, Jews and Gentiles alike.

Further Reading

To learn more about Jesus from both the Islamic and Christian perspective, please download your free copy of the book “Jesus: Man, Messenger, Messiah” from the Iera website (click on image below):

References

1 – The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church, p. 482.

2 – Justin Martyr, Dialogue of Justin With Trypho, Chapter 34.

3 Comments

great article , i wish that i can have a copy of your new book about jesus ???

i live in Canada .

thanks